The Tories Are Hiding: Why Were The Polls So Wrong In 2015?

The night of the general election in 2015 saw widespread shock on the faces of political campaigners, journalists and the public as the predicted hung parliament morphed before our eyes into a Conservative majority.

For months the polls had consistently shown Labour neck-and-neck with the Conservatives, leading to a slew of opinion pieces on how to navigate a hung parliament, what a minority government would mean for the UK, and whether Ed Miliband was quaking in his boots at the thought of having to work with the SNP.

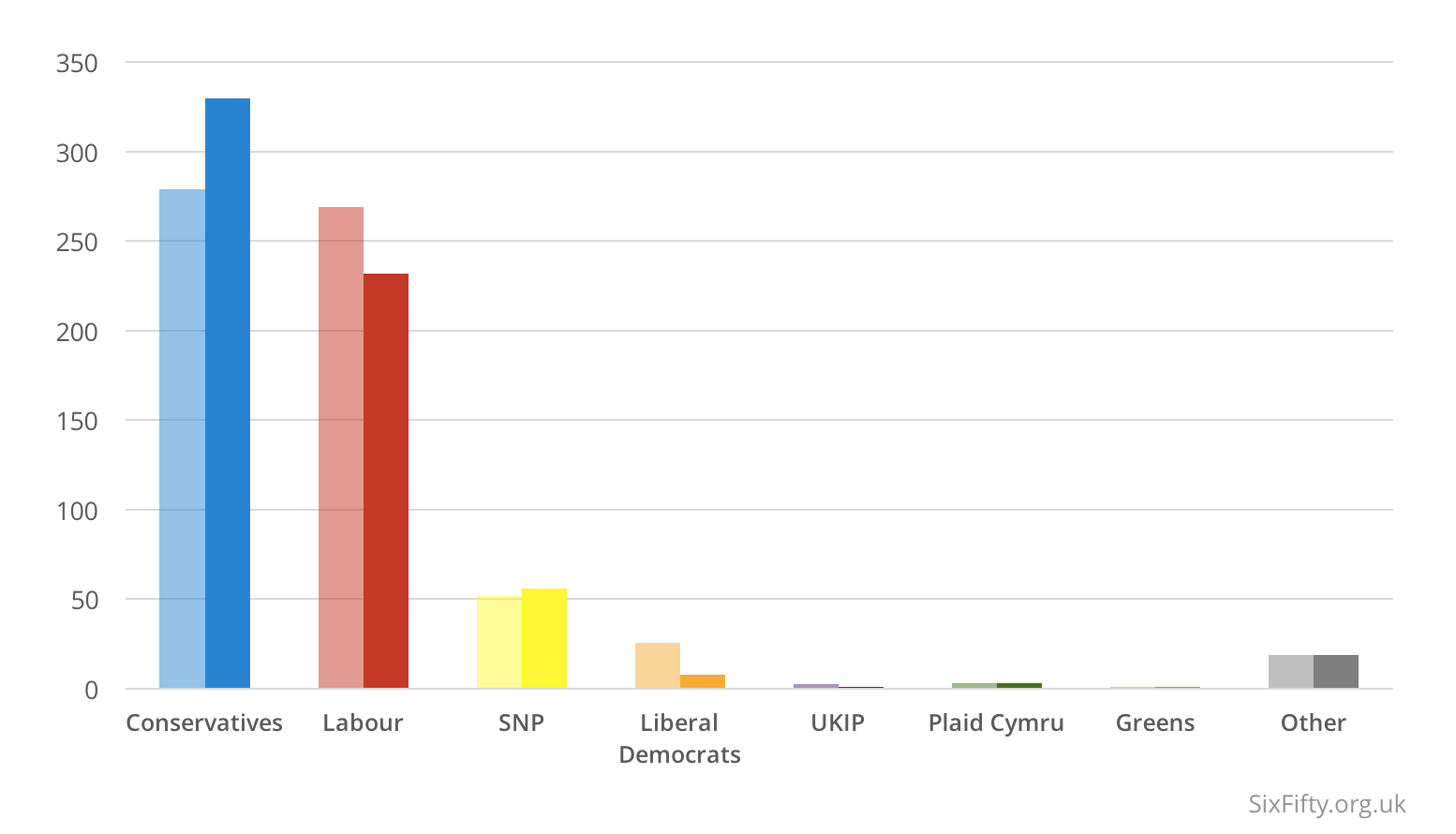

But the polls were incorrect: the Conservatives stormed ahead with 331 seats to Labour’s 232 and formed a majority government. Both of these figures were over 40 seats away from their predicted seat count – a huge margin of error. Although the vote share predictions for the other parties were reasonably accurate, we cannot ignore the fact that polling failed to represent the true state of our two major political parties.

Average forecast (left) vs actual results (right) for the 2015 general election 1

Average forecast (left) vs actual results (right) for the 2015 general election 1

Shy Tories?

Why did the polling companies get it so wrong? The phrase that was bandied about more than any other was the “Shy Tory effect” – people who are supposedly too embarrassed to admit their political leanings over the phone to a pollster, but will put their cross by the blue candidate in the privacy of the voting booth. The phrase was recycled from the 1992 election when the polls similarly failed to predict a strong Conservative victory.

The premise is that it is somehow unfashionable, misguided or downright gauche to reveal yourself as leaning Tory, and this stops people from telling pollsters their voting intention. However, this does not ring true. We all know plenty of strident Tories who aren’t afraid to ruminate on their love of fiscal austerity around the dinner table, and the Conservative party has no shortage of supportive volunteers.

Voting Conservative is well within the “acceptable” range of political viewpoints. Since 2015, we have seen the electoral success around the world of extreme right-wing parties, who make the Tories look positively fluffy – the way to get yourself uninvited to dinner parties these days is to be UKIP, not Conservative. The success of the Leave campaign in the EU referendum has made it mainstream to be Eurosceptic, and the Conservatives have commandeered this bloc.

If the shy Tory theory was true, right-wing voters weren’t telling the truth to pollsters - but it seems more likely that they’d just say they were unsure or wouldn’t be voting, rather than choosing a different party. Therefore, if this narrative was true we should have seen the polls underestimating turnout, and yet the opposite was true.

Madness in your method

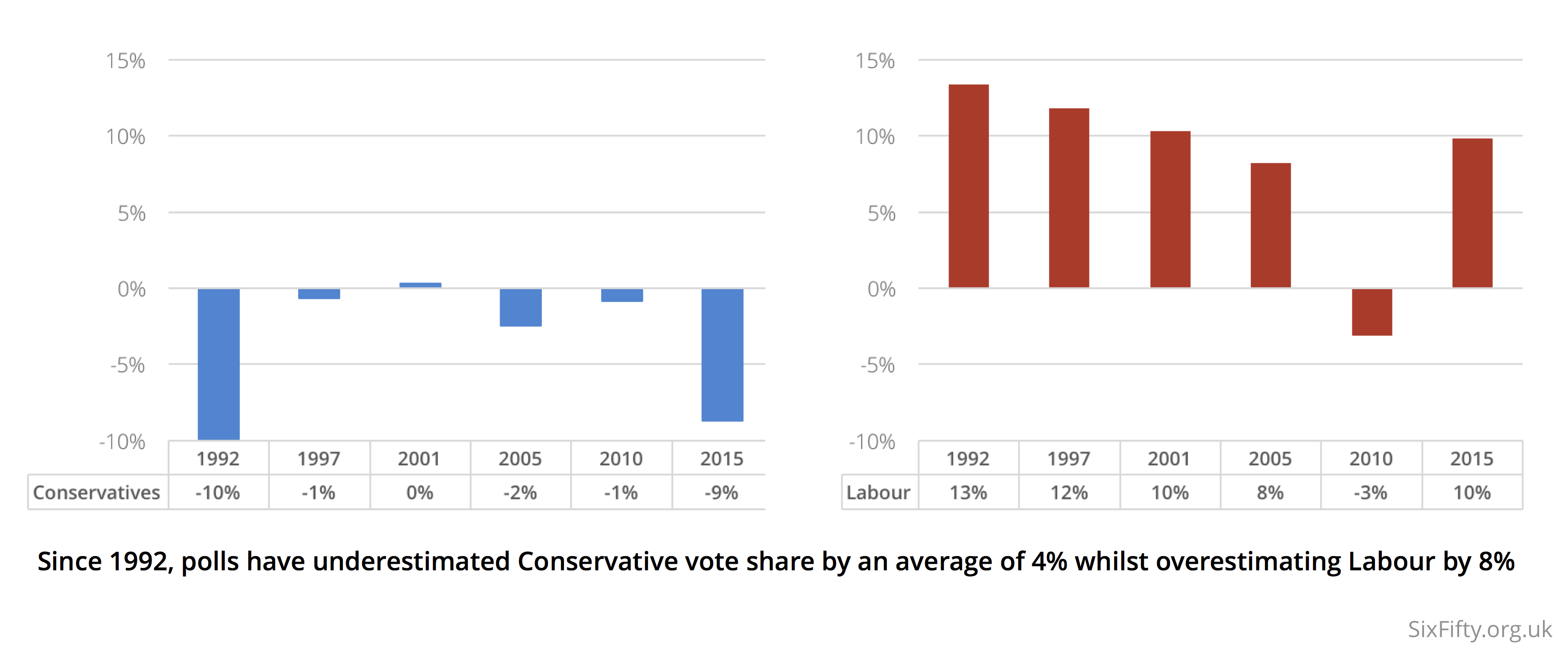

The underestimation of Conservative vote share is not limited to the 1992 and 2015 elections. In all but one of the last six general elections, the Conservative vote has been underestimated in opinion polls while the Labour share has been overestimated.

Polling averages prior to each of the last six general elections has favoured Labour over Conservatives 2

Polling averages prior to each of the last six general elections has favoured Labour over Conservatives 2

So what is going on? The lack of Tories can be better explained by the methodology used. The British Polling Council ordered an independent inquiry into the failures of pre-election polling in 2015, which concluded that polling companies had simply failed to reach enough Conservative voters.

For example, conducting polling online is less likely to reach older voters. This is a group who are less likely to have internet access, less likely to complete online surveys if they do, and yet far more likely to get out and vote Conservative. Younger people who do engage with online polls lean left, but are less likely to turn out to vote. This skews the polling away from the actual result.

Another problem is the skew amongst people who answer the door or pick up the phone to be polled. Simply put, those who are available at home during the day are more likely to be Labour voters, and those who are busy are more likely to be Conservative voters. This is a problem also seen in canvassing for political parties – their own numbers are likely to be biased depending on the time of day that they knock on doors. This is not a stereotype – the British Social Attitudes survey found that, after adjusting for age and social class, “busy” respondents skew Conservative (with an eleven-point lead) whilst easy-to-reach respondents are more Labour (with a six-point lead).

Furthermore, polling companies almost always use a regionally-balanced sample, but this does not take into account the seat targeting strategy used by the Conservatives in 2015. Campaigning focused on 80 key seats (40 of the most marginal Labour or Liberal Democrat seats to win, and 40 of the most marginal Tory seats to hold), and this meant that the national campaign was very unbalanced. The polls could not reflect this with a balanced sample and therefore did not reflect the number of seats won - vote share is less of a predictor for seat share when extensive targeting is used.

Make it right

Polling relies on people telling you the truth about how they are going to vote, as well as about whether they will actually turn out. It will always be fallible for these reasons, but the 2015 results should have shocked the polling industry into taking a closer look at methodology and bias correction, without relying on the convenient fiction of “Shy Tories”.

-

Source: Wikipedia’s collated table on “Final predictions before the vote” in their article on the United Kingdom 2015 general election. ↩

-

UK General Election results have been collated from Wikipedia. Polling averages are calculated as the average of all polls in the final week prior to the election using data from Mark Pack’s excellent PollBase database of historical opinion polls. ↩